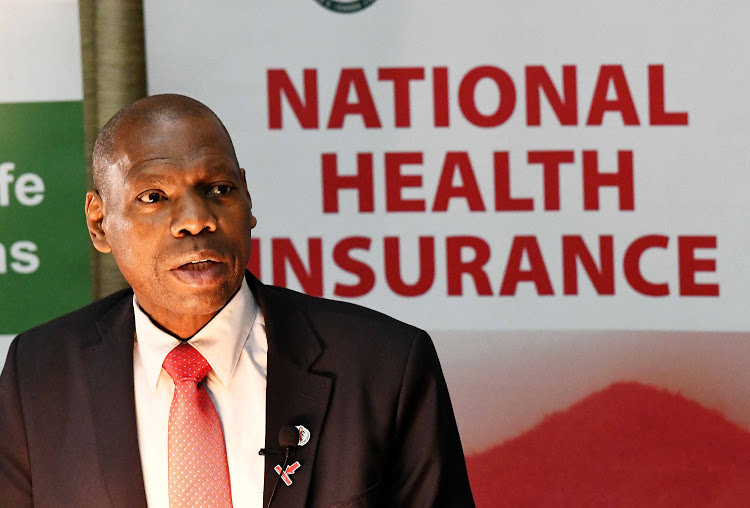

Health Minister Zweli Mkhize recently gazette two bills set to address both the exorbitant cost of private healthcare and the poor quality of public healthcare – namely, the NHI Bill and the Medical Schemes Amendment Bill.

On the latter, this week saw the release of the Health Market Inquiry report, a 265-page document that took five years and cost R196m to wrap up. (It cost roughly the same as has been spent on the NHI programme this year.) The inquiry recommended several reforms within private healthcare.

While government intends to have NHI up and running by 2026, with public hearings due to start in October, several questions remain unanswered. Fin24 spoke to public health expert Dr Lydia Cairncross to find out more.

Fin24: You note changes needed in both public and private healthcare. Can you expand on that?

Dr Cairncross: The health system in SA is in deep crisis, due at least in part to a massive burden of disease resulting from four concurrent epidemics: infectious diseases; maternal and child morbidity and mortality; trauma and violence and a growing burden of non-communicable, chronic diseases, including diabetes, hypertension and cancer.

This being addressed by a still largely divided and poorly resourced health sector.

The crisis in the public sector is well documented and publicised: lack of human resources, infrastructure and effective systems results in poor quality treatment, long clinic queues and unacceptably long waiting times for life-saving treatments. Historical apartheid inequalities are an ongoing reality.

The private sector crisis is a real and deepening one. Health expenditure through private intermediaries in SA makes up at least 50% of the SA GDP expenditure on health, making it proportionally the largest private health sector in the world.

This sector is staffed by the majority of general practitioners, specialists and sub-specialists but serves 16% of the population.

Issues include the rising cost of health insurance coupled with decreasing benefits; over-servicing of patients; unregulated and escalating costs; lack of coordinated and rational care due to excessive use of private specialists without an integrated network of general practitioners; lack of multidisciplinary teams; poor clinical auditing processes; excessive co-payments by users and lack of preventative health strategies. These issues are spiralling.

What will NHI look like for patients on a day-to-day basis?

The details are not yet clear. Patients will likely have one NHI card, used to register with a local primary care provider, public or private. It is not yet clear how it will be decided who this provider will be.

The primary care provider will then coordinate the holistic care of the patient. They will have access to all tests, investigations and procedures and arrange a specialist referral when required. They will also integrate care between specialists and be the main port of call for the user.

When travelling, NHI card users will be able to access treatment at other centres.

All eligible NHI users will be obliged to contribute to the NHI fund via taxation and a possible additional health tax. They will also be able to purchase ‘top up’ insurance. Once the NHI is fully operational, medical schemes will only be allowed to pay for services not covered by the NHI.

And for medical practitioners?

This depends on the type of medical practitioner and where they are currently located in the system.

Practitioners at public hospitals may need to significantly improve coding and recording systems to allow for remuneration for the hospitals from the NHI fund. Most practitioners in public facilities will probably remain salaried by a similar process to the current one.

Private general practitioners who contract into NHI will be paid on a capitation basis for service to a particular population. The burden and severity of disease in the community will be taken into consideration, calculating this capitation rate. Promotive and preventive practices will likely be incentivised.

Private specialists will have the option of contracting in to NHI. They will be reimbursed on a case-by-case basis, at a price to be decided by the Benefits Pricing Committee of the NHI.

How will the state accredit hospitals and doctors?

Accreditation will be through the already established Office of Health Standards Compliance which will assess and accredit all service providers, both public and private. Only accredited providers will be reimbursed under NHI.

The key issue around accreditation is that the last OHSC report painted a very concerning picture of the readiness of public health facilities.

Of 696 facilities assessed, only five met the benchmark for accreditation. The fact that the vast majority of public health facilities are currently not accreditable means that a massive upgrade and accreditation process must be undertaken to ensure that the public health system benefits from NHI resources. If this does not happen, NHI could paradoxically worsen inequality in some areas.

You support NHI broadly, with some points of critique and some questions. What are these?

There is an urgent need for progressive and far-reaching health system reform in both the public and private sector. The NHI is the current health sector reform plan on the table and we need to engage with it to ensure the best possible outcomes for healthcare in South Africa.

Positive aspects are the underlying principles, i.e. to reduce inequality in health service provision, provide quality care to all, promote primary health care and achieve universal health coverage.

The proposed cessation of tax incentives for medical schemes is positive in that firstly, it reduces ongoing subsidisation and support of private medical schemes by the public fiscus and secondly, it mobilises over R20bn which can be used to upgrade and accredit public health facilities.

Secondly, the plan to limit medical schemes to providing complementary care not covered by NHI is, for the first time, a clear attempt to limit the power of medical schemes. Of course, this will need to be within a context in where NHI is providing quality and accessible FitMenCook Epic Meal Prep: Bodybuilding Budget / Prep de Comida de oral steroids liquid muscle: the last word on milk and bodybuilding care for the services no longer paid for by private medical schemes.

A potential negative aspect of the NHI is, paradoxically, the potential to decapacitate the public health sector.

From international experience we know that only a public funded and managed health system can reliably and consistently deliver quality, equitable health care to the entire population.

The NHI plans to purchase (using public funds) health services from private and public providers. While this potentially gives access to increased resources in the private sector, these resources will still, particularly in the case of private hospital groups, be privately owned, for-profit providers.

If NHI does not specifically support, upgrade, capacitate and preferentially purchase from public providers, it runs the risk of further decapacitating public facilities as they may not be in a position to “compete” with the private sector.

If not managed in a pro-public sector manner, NHI could “outsource” large sections of health services, with potentially devastating effects on the public sector. The impact on NHI will very much depend on how this pro-public sector balance is achieved.

You previously said there were arguments for and against a purchaser-provider split, but that NHI could help kick off reforms. Can you explain?

A key issue with the establishment of a new fund is the potential for increased bureaucratisation of health care and potential overlap between the roles of the Department of Health and the NHI.

However, the complexity of healthcare in SA means it is not possible to fix either the public or the private system in isolation. Problems such as maldistribution of financial and human resources, and quality and accountability issues intertwined. The NHI proposal is an attempt to break down silos between public and private and find an integrated solution.

Whether it is successful or not will depend in part on the quality of the processes engaged by committees such as the Benefits Advisory Committee, the Benefits Pricing Committee and the Stakeholder Advisory Committee.